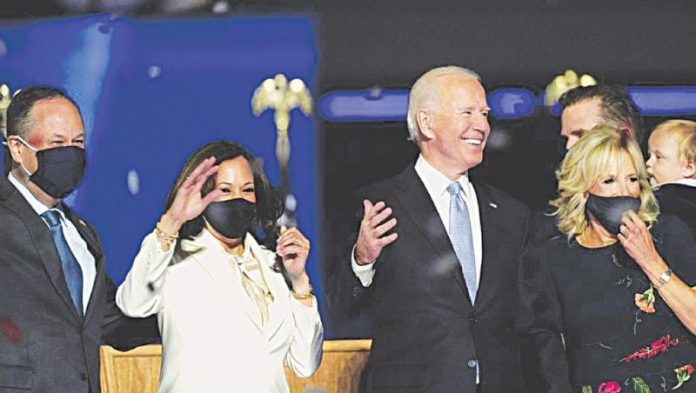

As Joe Biden, President-elect of the United States, settles in the driver’s seat after a bitterly-contested and divisive election in that country, the rest of the world prepares for a transition that many hope will restore institutional stability to the conduct of US foreign policy.

Like other states, Pakistan too has to brace itself for Biden’s four years. The obvious question is whether the Biden presidency will be any different for Pakistan than the Trump presidency or, more pertinently, Barack Obama’s two terms, when Biden was vice president.

To answer this question, let’s look beyond Donald Trump’s Twitter covfefeing perception to the actual conduct of his foreign policy. That should position us to analyse what US-Pakistan relations may look like under Biden.

What lies ahead

What is it that Trump did which Biden would not have done, or won’t do? The two men are as different as chalk and cheese, personality-wise. But, in many areas, Trump’s approaches — in substance if not in style — weren’t much different from traditional US policies: on China, North Korea, India, the Middle East, Iran (tougher), Israel (friendlier) and Afghanistan (closer to Biden’s Vietnam trap argument and ‘counterterrorism-plus’ approach than Obama’s decision to go for a surge).

Will Joe Biden’s presidency be any different for Pakistan than Donald Trump’s? What about Barack Obama’s? What can Pakistan expect and do to prepare?

Where Trump diverged sharply was on climate change, promotion of liberal values and rights and treatment of allies, especially Nato allies.

To put it differently, when Biden begins his term, he will change the course on issues where Trump diverged from standard neoliberal policies, while tweaking those where Trump sailed closer to the bipartisan consensus.

For instance, Biden is likely to ease up on Iran, while sticking to the fundamentals of the US’ approach to Iran, which sees Tehran as a troublemaker in the Greater Middle East and a threat to Israel. Similarly, Biden has constantly declared “an ironclad commitment to Israel’s security”, and it will be very unlikely that he could reverse Trump’s decision to declare Jerusalem as Israel’s capital.

Biden has talked about “end[ing] our support for the Saudi-led war in Yemen.” But it is unlikely that he could move away from Saudi Arabia, a policy that is structurally guided, given several factors in the Middle East. On China, he has talked about mustering the support of the allies (which Trump “kneecapped”) to counter the China threat. India has just signed the Basic Exchange and Cooperation Agreement, the final of the four foundational agreements with the US, and there is bipartisan consensus in Washington on India as a strategic partner. Not much is going to change on that count, unless Biden decides to take note of the grave human and religious rights violations in India.

Structural constraints limit a state’s foreign policy options and that is equally true of powerful states. Also, the conduct of foreign policy depends as much on exogenous actors and their actions as it does on institutional thinking within the state.

US-Pakistan relations

Let’s now return to our question apropos of Pakistan.

Pakistan’s relations with the US, even in the supposedly halcyon days of President Ayub Khan, were transactional. The ebbs and flows have depended on when the US has needed Pakistan and how Pakistan has managed then to take advantage of US needs to promote its own interests. The last 20 years were no different and the coming four years won’t be, either.

There is a reason for this. Strategic partnerships depend on a convergence of strategic issues and interests: geography, shared values, common threat perceptions, entrepreneurial innovation, market size et cetera. These factors in tandem, or in some combination, help states interact as strategic partners and denote positive engagement.

Not many of these factors have been in play in shaping US-Pakistan relations. The strategic interests of the two states, for the most part, have diverged; there are no shared values in the sense of what Samuel Huntington described as “western values” in his much-reviled The Clash of Civilizations; Pakistan isn’t exactly brimming with entrepreneurial innovation; the market size would have been substantial if not for low literacy and purchasing power and investment is hard to come by because of the investment climate.

The umbilical cord that has kept US and Pakistan connected for the past two decades, for good or bad, is Afghanistan. Afghanistan was close to Biden’s heart when he was vice president. But he had a different approach. By all accounts, he took an active interest in developments in Afghanistan. As Bob Woodward reported in his book, Obama’s Wars, Biden was opposed to the surge. He tried to convince Obama that a major surge would mean “we’re locked into Vietnam.” He wanted a narrow, ‘counterterrorism-plus’ approach: contain the Taliban, neutralise Al Qaeda (AQ) and get the troops home. Much has happened since then. The US signed a deal with the Taliban in February this year and, after much meandering, we now have an intra-Afghan dialogue which, predictably, has stalled. Meanwhile, violence flourishes unabated.

Pakistan’s relations with the US, even in the supposedly halcyon days of President Ayub Khan, were transactional. The ebbs and flows have depended on when the US has needed Pakistan.

The Trump administration lauded Pakistan for facilitating the process by getting the Taliban to the table and convincing them to start talking. But that is it. There’s not much else, or more, that Pakistan can do. And by the looks of it, Taliban are playing hardball. Additionally, there is the AQ and ISIS (the so-called ‘Islamic State’) threat in Afghanistan, as should be clear from the recent incidents of violence.

For now, the cord that binds the US and Pakistan to Afghanistan is intact. But if the talks remain stalled and violence continues, would Biden put the heat on Pakistan? That remains to be seen. The irony of the situation should not be lost on anyone: there’s only one US interest that binds Pakistan to the US and that can be a boon or a bane, depending on how the situation goes.

Finding common ground

So are there no areas where the US and Pakistan could find common ground? Fortunately, there are. But for that to happen, the Pakistan government will have to act more efficiently. Climate, healthcare, education and infrastructure development are some of the areas where Pakistan and the US could find common, non-politicised ground.

Biden was big on supporting The Enhanced Partnership with Pakistan Act of 2009 (commonly known as the Kerry-Lugar Bill). That’s the positive side of his neoliberal streak, which Pakistan could tap. The ministerial-level Strategic Dialogue (and the working groups) could be revived for both sides to work out the areas of cooperation.

With some deft diplomacy and lobbying, Pakistan could also test the waters with reference to Biden’s commitment to human rights. It will be interesting to see if he stays true to “Revitalis[ing] our national commitment to advancing human rights and democracy around the world,” with reference to India’s actions in occupied and illegally annexed Kashmir. That would give Pakistan an opening on Kashmir which, incidentally, is the central plank of Islamabad’s India policy since August 5, 2019.

Equally, Biden’s neoliberalism could also target Pakistan’s own acts of omission and commission with reference to human (including minority) rights, media freedoms, enforced disappearances, political dissent and civil-military relations. Biden’s support for the Kerry-Lugar Bill was grounded in the understanding that the US needs to move beyond just engaging the Pakistani military and get involved with the civil and political society. It will be difficult for Pakistan to expect Biden to take India to task while ignoring rights and constitutional violations within Pakistan.

The important point is that, going forward, Pakistan will have to become proactive. It cannot wait to see how Biden settles down. Islamabad needs to identify bilateral areas of cooperation and make an action plan for them. For that it can utilise its outreach into the Democratic Party, including by involving the diaspora.

That said, it is important to flag that the nature of US-Pakistan relations will also be determined by a practical approach on both sides. If the US thinks that it can wean Pakistan from China or get Islamabad to revise its regional approach, its policy will fail. While Pakistan does not want to be identified as being in one or the other camp, it has its strategic interests with China. It would like to enhance its relations with the US but not at the cost of its relations with China. In fact, it will be important to convince the US that Pakistan’s engagement with the China Pakistan Economic Corridor does not mean it is disinterested in US public and private investment that can target key sectors in Pakistan’s economy and help Pakistan develop. It will welcome any such investment.

Similarly, if Pakistan is expecting that the US will come down hard on India and make Kashmir the central point of its (US’) South Asia engagement, Pakistan will be disappointed. Ditto for expecting high-end military systems and platforms from the US.

On more than one occasion in his appearances on my television programme, the current National Security Advisor, Dr Moeed Yusuf, has stressed geoeconomics as the key to Pakistan’s national security approach. Going by that, for relations to be useful, both Pakistan and the US will have to find areas where they can cooperate meaningfully, and in ways that can move relations out of their transactional mode to make them strategic.

Biden’s presidency offers both sides a chance to go for a reset. That is possible if the two sides lower their expectations with reference to what each can do for the other on issues of hard security. On the other hand, if they can broaden the definition of security to include areas identified above and sequester them from hard-security concerns, the relationship could develop more abiding structures for strategic engagement.